National Nutrition Guidelines vs Common Diets. What’s the Difference?

By Dan Speirs

‘Go Paleo’, ‘Keto is king’, ‘eat clean’, ‘save the planet – become a vegetarian’. Or very occasionally, ‘follow the science – use the National Nutrition Guidelines’!

After 25 years working in fitness/fitness education, ‘nutrition’ is without doubt the most consistently contentious topic I’ve encountered. Nothing else divides people causing them to passionately advocate for the particular camp they align with. Now passionate advocacy is great – especially if it relates to something that benefits the health of our communities. The problem with passionate advocacy however is that it can blind us to the bigger issues.

So, to try and put nutrition and diet into perspective, this article will:

- Review the key messages from the Ministry of Health’s (MoH) Eating and Activity Guidelines for Adults (updated in 2020)

- Identify the consistent messages across these guidelines and a range of common diets

- Highlight the major health-related dietary issues facing the population

- Shine a light on the action (or lack thereof) being taken to address these issues

- Present a thought-provoking video that sums the current situation up ’uncomfortably’.

Before we proceed, here’s an important qualifier – this article focuses on diet and nutrition for general health, not athletic performance which we cover elsewhere.

The National Nutrition Guidelines

The Ministry of Health’s (MoH) Eating and Activity Guidelines for adults were updated in 2020. Moving away from specific guidelines, the MoH produced a set of general recommendations for what people need to eat or do. The recommendations are based on nutrient intakes and activity levels known to be consistent with good physical health. According to the MoH, their recommendations can be applied broadly – to guide health promotion programmes, or to help individuals choose healthy eating patterns.

It’s important to note that these recommendations aren’t just randomly generated from an office in Wellington. They are regularly updated, evidence-based recommendations built from a substantial body of national and international research. Their development is directed and overseen by a Technical Advisory Group made up of Māori and Pacific experts, and leading researchers and practitioners from the fields of public health, medicine, nutrition, and physical activity.

Six eating statements are included in the recommendations. We’re focusing on the first four here. The last two statements are specific to breastfeeding along with food preparation and storage practices to protect from illness.

Eating statements 1-4:

- Enjoy a variety of nutritious foods every day including:

a. Plenty of vegetables and fruit

b. Grain foods, mostly whole grain, and those naturally high in fibre

c. Some milk and milk products, mostly low and reduced fat

d. Some legumes, nuts, seeds, fish, and other seafood, eggs, poultry and/or red meat with the fat removed - Choose and/or prepare foods and drinks:

a. With unsaturated fats instead of saturated

b. That are low in salt, and if using salt, choose iodised

c. With little or no added sugar

d. That are mostly whole and less processed - Make plain water your first choice over other drinks

- Any alcohol consumption is risky, so if you drink alcohol, keep your intake low.

NB. ‘Low’ alcohol intake = no more than 2(female)/3(male) standard drinks per day or 10(female)/15(male) standard drinks per week.

The MoH notes that their more prescriptive guidance from previous years (ideal serves per day of the food groups) is still valid. They’re actually included in the 2020 updates, albeit relegated to the appendix.

Now based on how contentious nutrition is, you’d expect the MoH statements to conflict with the more common dietary trends. Let’s see if that’s the case.

National nutrition guidelines vs common diets – not as different as you might think!

In a completely unscientific analysis, we compared the major messages from five common diets/dietary patterns against the MoH’s eating statements. We awarded:

- Two ticks when diet messaging appeared to be completely consistent with the MoH statements

- One tick when the messaging was somewhat consistent

- A cross (and no points) when the messaging conflicted with the MoH statements.

The common diets we looked at were:

- The Paleolithic (Paleo) Diet. Paleo advocates eating whole foods and avoiding grain and diary foods because this ‘replicates’ the way our distant ancestors ate (apparently)

- The Ketogenic (Keto) Diet. Keto advocates reducing the intake of carbohydrate foods (carbs) to induce a state of ‘Ketosis’. Ketosis is where the body uses fat rather than carbs as fuel

- The Vegetarian Diet. People following a vegetarian diet generally avoid all meat, fish, and poultry

- The Mediterranean Diet. This diet encourages the consumption of a wide variety of whole foods, especially fruit and vegetables

- Intermittent Fasting (5:2 diet). The 5:2 diet advocates consuming a normal (ideally healthy) diet for 5 days, followed by a 2-day fast.

Here’s what our analysis revealed:

National nutrition guidelines and common diets tend to say the same thing!

First up, here’s rationale for our scoring:

- Intermittent fasting scored 20/20 on the assumption that a ‘healthy eating plan’ is followed for the 5 non-fasting days

- The Keto diet received one tick with regard to fruit and vegetables because while it allows green vegetables to be consumed, it excludes all fruit

- Keto and Paleo diets received crosses with regard to the intake of grain foods because these foods are explicitly excluded

- Regarding the consumption of milk and milk products, Keto received one tick because it does allow consumption of these products although not low or reduced fat versions. Paleo received a cross because it recommends their exclusion

- While Keto and Paleo recommend using some vegetable oils, their focus on animal foods links to a higher saturated fat intake – 1 tick only

- Vegetarianism received two ticks with regard to the protein rich food groups that include animal products because when well-managed, plant sources (legumes, nuts, seeds) and non-meat foods such as eggs, provide adequate sources of protein and essential minerals.

And here’s a summary of our findings:

- The major diets were more consistent with the MoH statements than conflicting

- Most of the diets recommended consuming plenty of fruit and vegetables

- The consumption of unrefined grain products is recommended by all but Paleo and Keto

- All of the diets recommend:

- Moderation or avoidance of alcohol

- The consumption of whole as opposed to processed foods

- Prioritising water over other beverages

- The consumption of foods with little or no added sugar or salt.

There is clearly a degree of consistency across the MoH recommendations and these common diets. However, the important question is – does this consistency reflect New Zealand’s actual nutritional intake?

What are the main issues with our nutritional intake?

You might have heard the expression ‘You can’t see the forest for trees’. It refers to a person who is so caught up in the detail of something that they don’t notice what is important about the thing as a whole.

Are we so caught up in the detail of nutrition, macro and micro-nutrients and which diet is superior, that we’re missing the big issues?

The New Zealand Health Survey of 2020/21 revealed that:

- Only 30% of New Zealand adults consumed the daily recommendation of at least 3 serves of vegetables and 2 serves of fruit. This recommendation has actually now increased to 5-6 daily serves of veggies – so ‘30%’ is ‘generous’

- 20% of the adult population classified as hazardous drinkers.

As well as the NZ Health Survey, the Eating and Activity Guidelines inform us that:

- Only 10-14% of adults ate the recommended ‘heavy grain breads’ (wholegrain, wholegrain rye) with the majority eating more refined grain foods

- New Zealand adults are regular consumers of sugary drinks

- 50% of adults choose low or reduced fat milk and dairy products

- The majority of adults are regular consumers of fish, chicken, and red meat.

Additionally, EFTPOS data collated by the Helen Clark Foundation and published by Stuff revealed that in Auckland alone, residents spend over $1 billion annually on fast-food. This equates to approximately:

- 143.3 million Big Macs or

- 639 million KFC Wicked Wings or

- 112 million Domino’s Pizzas.

The fast-food giants are doing very, very well!

Expressed another way, this fast-food spend equates to:

- 89 Big Macs, or 399 Wicked Wings, or 560 slices of Pizza for every adult, child, and baby in Auckland, every year!

The reality is, at a population level we consume far too much fast food, processed food, sugary drinks and alcohol, and not nearly enough fruit and vegetables, whole foods, water, and lean, low-fat foods. While some diets advocate for the consumption of more animal foods (for extra protein), our general consumption of such foods is more than adequate. Indeed, it has been observed that if the rest of the world ate like the average kiwi (lots of red meat) we’d need another planet to sustain us!

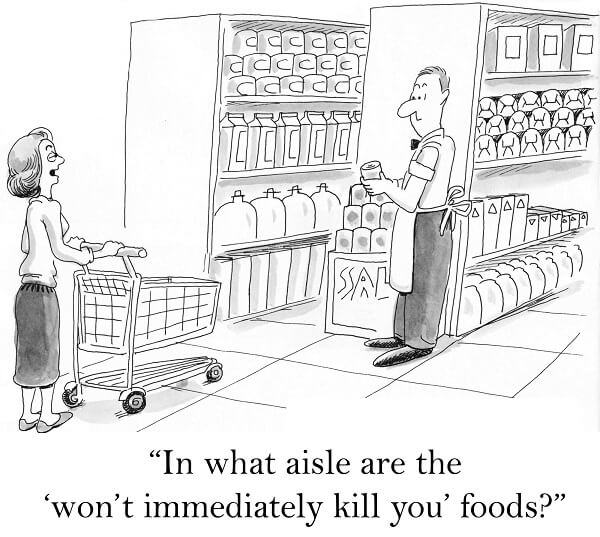

I think its time we put the low vs high carb/protein/fat debates to bed. They’re not helping us. After all, if we advocate ‘low carb’ eating are we actually saying eat even less fruit and vege than we are currently? Note – for those who aren’t aware – fruit and vege are a primary source of carbs, along with an assortment of other essential micro-nutrients. Are we saying that it’s OK to drink more beer as long as we choose a low carb version? Are we saying the KFC double down is a good food choice because it’s ‘low carb’ (with the bun removed)?

We get bogged down and confused when we argue the detail of optimal macro-nutrient intakes. People eat food after all, and it’s clear what types of food we should be eating more or less of. Let’s keep it simple, and focus on helping people to improve their intake of real food.

We need to re-focus…on the food environment

Don’t get me wrong, developing a detailed understanding of nutrition and dieting is important. That’s why we include substantial modules on these topics in our core Personal Training and Weight Management programmes. Building your knowledge in these areas enables you to understand the consequences of a poor diet and see through the spin used to sell diets in general. However, knowing about diet and nutrition doesn’t translate into being able to change peoples eating behaviours. A point that was acknowledged many years ago.

In 2004, in response to growing concerns about obesity, the MoH published Tracking the Obesity Epidemic. Produced by a group of concerned public health experts, the report highlighted that:

- To achieve sustainable change, policy intervention would be required to reduce the obesogenicity of the environment.

The report made it clear to policy makers that simply communicating messages about healthy eating wasn’t enough. Yet, this is exactly and only what successive policy makers have done. And, there’s no sign of this changing anytime soon.

All the while, the community greengrocer that was common 20-30 years ago has disappeared. Rather than having a convenient source of fresh, affordable fruit and vege, we now have an abundance of fast-food outlets. Additionally, our supermarkets and dairies incentivise consumption of ultra-processed products loaded with extra sugar, fat, and salt – they are more profitable and rarely perish.

Quite simply – it’s not nearly as easy to eat healthily today as it was 20+ years ago.

The environment we live in shapes our behaviour more than our knowledge of what is healthy.

Professor of public health at AUT and former health and nutrition advisor to the Government, Grant Schofield, refers to the modern food environment as the pathological driver of obesity, tooth rot, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s, heart disease and many mental health problems. Increasingly, areas (predominantly lower socioeconomic) in many of our cities are referred to as fast-food swamps.

The reality is that the environment we live in shapes our eating behaviour more than our knowledge of nutrition. And, because we can’t rely on the Government to step in and make change, we need to start tackling this environment ourselves.

In upcoming blogs we’ll share some techniques from our Weight Management programme that can be used to combat the modern food environment. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this thought-provoking YouTube video. Yes, it’s presented by an American and it talks to an American audience in 2015. Unfortunately, we mirror many of the less desirable characteristics of US society. What was relevant there in 2015, is relevant here in the early 2020s.

Why we can’t stop eating unhealthy food – TEDMED

Use Your Passion for Fitness to Change Lives

Improve your own training, become a Qualified Personal Trainer and make a real difference in people's lives. Enquire now to find out more.

Absolutely shameful that NZ has alcohol recommendations apparently set by alcohol lobbyists. They are ridiculously high.