Exercise Behaviour is More Important than Just Working Out

Home » Fitness Training »

By Dan Speirs

Exercise programmes are normally initiated with great gusto! 💥

Motivation is usually high when people come to action as losing weight, improving health, or getting stronger gain priority over other activities.

However… time and again the same patterns repeat – motivation dwindles as priorities shift and soon enough exercise becomes an occasional activity at best; ‘next time I’ll try harder.’

The pattern of engagement and disengagement manifests in the attendance (who shows up) and retention (who re-joins) data of fitness clubs worldwide. Highly motivated new members attend regularly over the first few weeks of their membership.

Initially, motivation gets them through and by attending they benefit from the support and encouragement of gym staff. But as motivation dwindles, the barriers that were initially able to be overcome start to interfere and attendance dries up. Without attendance, there is less opportunity to be noticed by, and gain the support of the gym staff.

This problem occurs because we treat behavioural science as the unpopular cousin of exercise science. Exercise programmes and WODs (Workouts of the Day) command more attention than the awkward, ‘touchy-feely’ stuff of trying to understand and support people.

For the vast majority, exercise behaviours don’t just happen; they need to be built. Unless they are built, with intent, people have little chance of gaining the benefits that exercise offers. In this sense, working on behaviour is more important than just ‘working out’. Because without one, the other seldom happens.

It’s for this reason that understanding human behaviour is a core component of our Personal Training programme.

If we’re going to help others gain the benefits of exercise (or gain those benefits for ourselves), then we need to spend some time learning about how behaviours are built.

To understand behaviour, you need to look under the hood

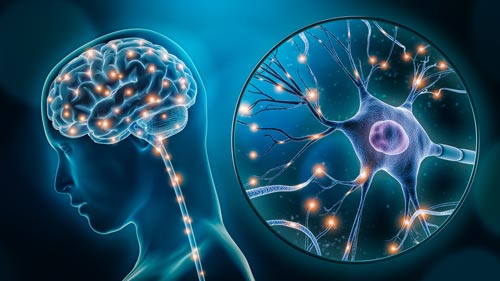

Everything we do, think, and feel is governed by one organ – the brain. Weighing in at little more than 1.3kg, this phenomenal organ:

- Makes up less than 2% of the average humans bodyweight but demands 20% of the body’s energy

- Is made up of approximately 86 billion (86,000,000,000) functional units (neurons), and 85-86 billion glial cells which support those neurons

- Has trillions of connections between neurons (synapses), over which information is communicated

- Has over 100 specialised chemicals (neurotransmitters) which pass information from neuron to neuron; some increasing communication, some reducing it, and some ‘balancing’ it out to moderate our moods and behaviours.

There’s more to the brain than what’s on the surface

The capacity and complexity of the human brain is staggering; so for this small section we’re going to limit ourselves to looking at the differences between what’s known as the cortex vs. the sub-cortex, and the concept of the conscious vs. subconscious brain, as they relate to efficiency and behaviour.

The cortex (known correctly as the cerebral cortex) refers to the superficial layer of the brain. It’s distinguishable by the ‘hills and valleys’ (sulci and gyri) we see when we look externally at a brain. Higher level functions such as planning, problem solving, reasoning, evaluation and critical thinking occur in the cortex, in particular its frontal regions. As such, neuroscientists refer to the cortex as ‘the seat of consciousness’.

Consciousness refers to the portion of our reality that we feel aware of and in direct control over.

It’s important to note that the cortex has an average thickness of only 2.5mm (yes, millimetres, not centimetres). Quite simply, there’s a lot more to the brain than what’s on the surface. The vast majority of the brain is sub-cortical (beneath the cortex). Where the cortex is considered the seat of consciousness, the sub-cortex is home to the ‘subconscious’. This refers to the portion of our reality that we are not fully aware of, or do not feel that we have direct and complete control over.

The iceberg analogy is useful here; the tip of the iceberg represents the cortex and our consciousness, while the bulk of the iceberg represents the sub-cortex and our subconscious.

Most of what we do, think, and feel is governed by the sub-cortex and our subconscious

Consider walking home from work. Consciously, I might be planning my key work tasks for the following day. Subconsciously, my brain will be receiving and acting on masses of sensory information from the environment.

In response to fading light, messages will be sent to my pupils telling them to dilate and allow more light to enter the eye. The action of hundreds of muscles will be perfectly regulated to enable me to move fluidity as I walk over different terrain.

My heart and breathing rates will be regulated to provide my muscles with fuel and expel waste products (CO2). And without consciously thinking about it, my mood could range from upbeat and happy through to sad and depressed depending on any number of factors from my past, present, or perceived future.

Creating an exercise behaviour requires control to be transferred to the sub-cortex

The reason that most neural activity occurs in the sub-cortex boils down to efficiency.

Higher level conscious tasks demand a lot of energy to deal with the unknown or the complex. At a neural level, thousands, if not millions of connections need to be made, broken, and/or refined in the process of learning how to address such tasks.

In comparison, the simpler tasks controlled by the subconscious brain are far more efficient. At a neural level, the connections have already been made and refined; there is no need to waste energy through the process of learning or analysis. These tasks occur efficiently, when necessary, without requiring permission from head office (the cortex). In the case of regulating the heart or breathing rates, the benefit of this should be reasonably obvious; you don’t want delays when it comes to essential functions.

When it comes to building a new exercise behaviour, the initial planning, implementation, and problem-solving tasks involve conscious activity in the cortex. However, the ability to fulfill the mission of creating a behaviour depends on how well control of the behaviour can be transferred to the sub-cortex; because in our modern, high stress society the capacity restricted cortex has a never-ending list of demands placed on it.

If we want to help people build sustainable exercise behaviours, the more automatic or ‘habitual’ we can make those behaviours, the better.

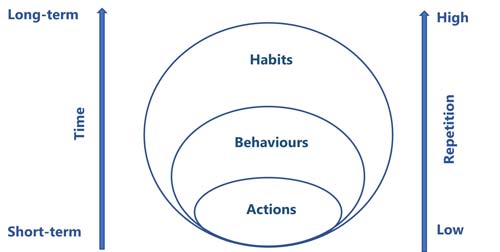

Behaviours are built through repeated actions

Exercise behaviours always start as individual actions. Unfortunately, many ‘would be’ behaviours don’t make it past this action stage. Actions refer to things we do once, twice, or even a few times, but not consistently. Going for a run is an action, going to the gym to workout is an action. These actions can’t be considered as ‘behaviours’ until they are repeated consistently over time.

At the neural level, such actions are governed by the conscious brain; they’re novel and require elements of planning, problem solving, and reasoning to enact. The neural pathways/connections that enable the action to be completed are in the process of developing. The thinking at this stage could be ‘I’m going to the gym tonight because I really need to get fit and drop this winter fat. I need to remember to pack my gym gear and a towel and a pre-workout snack’.

It can feel like a lot of effort is required at this stage to enact the action; so, it’s just as well that motivation is (usually) high to counter the negative perception of effort!

Neural connections are developed, refined, and strengthened through repetition

In contrast to actions, behaviours are consistently repeated actions. If a person goes to the gym, as intended three times a week, and they’ve done this consistently for the past six weeks then we could say that they’ve built an exercise behaviour. If such a behaviour was continued for a period of six months, we could then say that an exercise habit (consistently repeated behaviour) had been built.

‘Building’ is the correct term because at the neural level building is exactly what is happening.

With each repetition of the action, neural connections are being developed, refined, and strengthened as the neural pattern of ‘going to the gym’ gets programmed into the brain. As the programme is refined, it becomes increasingly automatic and less dependent on input from the conscious brain. It feels ‘easier’ for the person involved as less thought and planning is required.

Neurally, the progression from action-behaviour-habit equates to the progression of control from conscious-semiconscious-subconscious. Habitual exercisers often observe that exercise for them ‘just happens’; there is no thought or planning involved.

As repetition is key to building exercise behaviours and eventually habits, the key question becomes; how do we make exercise repeatable so that a strong neural pattern gets wired into the brain and the behaviour becomes automatic?

To build an exercise behaviour, make exercise easy to repeat

In the early stages, building an exercise behaviour has more to do with behavioural science than exercise science.

The science of sets, reps, and intensities can be focused on once a person is exercising consistently enough to benefit from them. Prior to this, the focus needs to be on making exercise easy to repeat. In this context, easy means removing the potential barriers that might interfere with the emerging behaviour, whilst making the exercise experience as pleasurable as possible.

At the core of behavioural science lie what practitioners refer to as the ABCs (Antecedents – Behaviour – Consequences). Quite simply, behaviours (or actions) are more likely to be repeated when the consequences attached to them are pleasurable.

In an exercise context, pleasure is subjective; what appeals to one person with regard to the setting, type, duration, and intensity of exercise may not appeal to others. To make exercise repeatable, an investment of time must be made to discover the preferences of new exercisers. The exercise experience must then be tailored to those preferences, a point we emphasise in our Personal Trainer programme.

A new exerciser should never be prescribed or made to engage in exercise they dislike, no matter how technically superior the experts or celebrities claim a particular exercise to be.

Exercise only works if people do it and do it consistently.

For most, the achievement of goals is a rewarding experience that helps to reinforce an emerging behaviour.

As such, process goals such as ‘attend three classes this week’ as opposed to outcome goals such as ‘lose 5kg’ should be established with new exercisers. Process goals are those that the person has much more control over. If these goals are measured frequently and celebrated when they are achieved, they help to build a ‘can do’ belief in the new exerciser. In contrast, the potential non-achievement of an outcome goal could have the opposite effect.

In a fitness club setting, staff should never underestimate the positive impact of noticing, welcoming, and congratulating new exercisers for simply attending. It’s a lot easier to repeat exercise when people know they’re going to a friendly, helpful, and welcoming environment where their presence is noticed, and they feel valued.

In our increasingly hectic world, we can’t always rely on memory to remind us to ‘go for a run’, or ‘go to the gym’.

To make sure that exercise sessions don’t get missed, behavioural prompts specific to the individual should be used. Fortunately, the world of smartphones makes it easy to set prompts, such as a reminder to ‘pack gym gear’ the evening before a scheduled session. A reminder to ‘have a snack’ in the afternoon could ensure that an after-work class isn’t missed due to low energy.

Personal Trainers should always be sending reminder messages to clients the day before a scheduled session.

Barriers to exercise need to be identified and removed

A major impediment to the establishment of an exercise behaviour is the existence of barriers that could interfere with the new behaviour. Common barriers include perceived time, money, hassle, and any unpleasant experiences. Left unaddressed, barriers manifest in missed sessions and absence from the gym. Behaviours can’t be built if repetition doesn’t occur; new exercisers in particular need help to identify and remove the obstacles that hinder their progress.

An exercise programme lasting one hour, written for a person with only 45 minutes to spare is a barrier. A technically advanced programme is a barrier for a new exerciser who feels awkward trying to complete something that is beyond them. Scheduling an exercise session at a time of day that doesn’t suit a person also creates a barrier.

Making exercise easy to repeat requires time being spent with new exercisers identifying and removing potential barriers.

In a fitness club setting, the non-attendance of new exercisers needs to be noticed for what it is and acted on as a priority. Left unaddressed, a simple barrier that could be removed via a phone call and appointment to modify an exercise programme, will manifest in a disgruntled member having no intent to renew their membership, or recommend the fitness club or personal trainer to others.

A relationship of support needs to be formed and nurtured with new exercisers…

For people to gain the full benefits of exercise, exercise behaviours need to be built. Via the process of repetition the brain programmes behaviours into its structure.

If repeated consistently over a long enough period these behaviours start to run automatically. To enable this to happen, a new exercisers preferences need to be identified and catered to. Process goals need to be established, measured, and celebrated. Behavioural prompts need to be used, and barriers to exercise need to be removed. Failure to do so means that success with exercise boils down to little more than good luck.

At the fitness club, a relationship between staff and the new exerciser must be formed and nurtured. This enables help to be provided easily, at anytime that it’s needed. It also enables attendance and adherence problems to be identified early and resolved promptly and positively.

For new exercisers and/or those who are supporting new exercisers, refer to the checklist that follows; if the answers to any of these questions isn’t a resounding ‘yes’ then changes need to be made:

- Is the type of exercise that is planned, enjoyable or likely to be enjoyable?

- Will the time of day and duration of the exercise be easy to fit into the persons day?

- Has the planned exercise been scheduled to avoid competing with activities that the person currently loves doing?

- Is the venue for the planned exercise easy to get to and nice to be at?

Use Your Passion for Fitness to Change Lives

Improve your own training, become a Qualified Personal Trainer and make a real difference in people's lives. Enquire now to find out more.

Hi Dan – at an elementary level you would have to accept with the best intentions many people are discontented with the way they present.

The symbiotic relation between trainer and customer is bound to fail & as you state the wayning effect occurs after the realisation that to “ change “ places significant demands that require sacrifice beyond conventions of day to day life.

The commitment must be complete.

Diet, life style, psychology + motivation equate to the dilemma and sustainability.

Burst and HIT intervals – increasing HGH ~ 400% and insulin resistance, opening the cell door plus degradation of DNA helix & frayed telomeres .. to name but a few.

Can be all part of the complexities of health and fitness which I am interested in with particular rules I apply to myself.

Cheers Warwick

Hi Warwick, thanks for your comment. With regard to intentions, I think that in the vast majority of cases, trainers and new clients approach this with the best of intentions – they’re both wanting success via exercise and the achievement of goals. And both parties are committed to the cause. But goals are seldom achieved without repetition, without the building of a sustainable exercise behaviour that fits the individuals circumstances. This is sometimes where the disconnect exists – fitness professionals built their exercise behaviours years ago, often through a love of physical activity/sport. Regular exercise became a priority. In contrast, many new clients haven’t built an exercise behaviour, exercise hasn’t been top of the priority list , and it currently competes with a mix of other priorities. As such, rushing to incorporate exercise science (HIIT intervals etc) can result in a vital stage being missed – finding out about a persons preferences, availability, and capability with regard to exercise, and catering prescription to these factors as a priority. And providing support to make exercise enjoyable, and to remove barriers to participation as they arise. Once a regular behaviour is built then the prescription can become more elaborate. We sometimes rush to the elaborate stage, neglecting the building stage.